The photos are striking reminders of human resilience: one house juts out from the middle of a highway, another, like a nail in a board that refuses to be hammered down, stands alone in a field of rubble.

These “nail houses,” owned by people in China who refuse to sell their property in the face of corruption and government power, are documented in a VICE story from this past August featuring Stephen Hess, a Transylvania University political science professor. Last month, he also was interviewed by the International Power Hour podcast about his research on protests in China — and his writings are appearing in several books.

Hess told VICE that nail houses have “captured China’s imagination because they represent a ‘David and Goliath’ struggle. Nail house protests really resonate with the Chinese public because of the wide perception that local officials are corrupt and collude with developers. The movement has come to symbolize the growing ‘rights consciousness’ within China, as citizens stand up against local officials who are misusing their offices.”

In the International Power Hour podcast, Hess contrasts mainland protests such as these with the Hong Kong demonstrations against Chinese authority. There’s a certain routineness about protests in China’s interior, and they’re usually localized, targeting issues in people’s own backyards, Hess said. They also tend to be framed in a way that’s supportive of the national government.

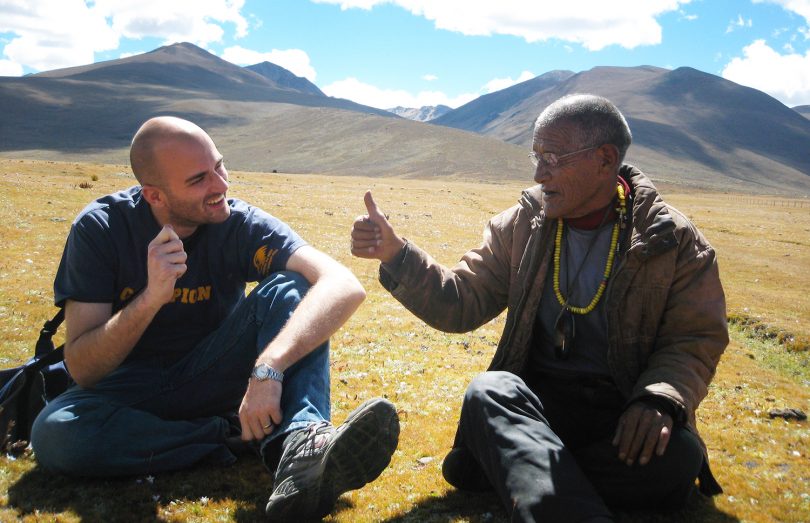

Hess gained valuable insights into Chinese culture and politics while teaching as a Peace Corps volunteer in southwest China. He now coordinates Transylvania’s Peace Corps Prep program.

His expertise on the country also was called upon a few years ago when he appeared before the congressional U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

Additionally, Hess has been involved with several book projects, including “Authoritarian Landscapes: Popular Mobilization and the Institutional Sources of Resilience in Nondemocracies” (2013) and the co-authored book “Charting the Roots of Anti-Chinese Populism in Africa” (2015).

Hess is also contributing a chapter to a book in the works titled “The Political Logic of the U.S.-China Trade War” on the trade war’s domestic implications in China. Topics include an exploration of what motivates President Xi Jinping in the trade negotiations as he tries to quell unrest, reform the economy and root out corruption at the local level. Is it important for him to make a deal with the United States? Is he concerned about his country projecting power internationally — or protecting the regime?

“China is becoming a geopolitical player with influence all over the world, but all of that is really secondary to the main concern, which is keeping the party in power,” Hess said.