Brazil will mark the bicentennial of its political independence today, but for many Brazilians it has been difficult to generate much excitement to celebrate the great date. Despite the country’s strong public health tradition and its high vaccination rate, its experience of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a brutal one, its almost 700,000 deaths second only to the United States. As it faces the same inflation worries as much of the globe, the strong economic growth it enjoyed in 2021 in the aftermath of the worst of pandemic-related woes has faltered this year. And the health of its democracy is in a similarly worrying state, as President Jair Bolsonaro publicly questions the integrity of the electoral system on the eve of his reelection bid while his opponents inside and out of government accuse him of attempting to politicize the military and of encouraging the spread of conspiracy theories via social media.

Against this backdrop, commemorations of the bicentennial have been subdued; a few major events are scheduled for the bicentennial date, but even those planned by the federal government are “routine” and “discreet,” according to the newspaper O Globo, and there has been little public appetite for celebration. As the journalist Fernando Canzian put it in a pessimistic survey of the country’s recent economic performance, Brazil at the bicentennial feels “aimless,” a country “of crises and near stagnation” with “no long-term project” for development.

In some respects, the country’s current difficulties, from the coronavirus to WhatsApp groups, seem quite contemporary. But they also evoke its centenary in 1922, which itself came in the continuing shadow of global crisis, in the form of world war and the 1918 influenza pandemic. In Brazil the year was one of political turmoil. The country was far from democratic, and citizens’ suspicion of the political system was deepened by the fact that the year’s presidential election took place amid accusations that the winner, Artur Bernardes, had insulted the military in a series of letters published in a Rio newspaper. The letters proved to be forgeries, a hundred-year-old example of truly fake news. Still, the controversy helped poison the relationship between the new government and young officers — some of whom staged a failed rebellion in July and continued their armed struggle in the ensuing years — as well as the press, whose freedoms were regulated and curtailed in a 1923 law.

In fact, though the national government planned major events to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the country’s political liberty, including a world’s fair-style international exhibition, the centenary date came during a state of siege which severely limited citizens’ rights. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Brazilians were ambivalent about the milestone, one prominent politician pointing out that only “two or three” of the year’s commemorative events could be “considered popular,” and despite massive investment, the fair was a disappointment, pavilions “empty” and displays “unstudied,” according to its official magazine. Instead of celebration, many Brazilians preferred to use the centenary as a rhetorical and moral cudgel against a social and political system from which they felt alienated, arguing that what the nation had to show for 100 years of independence was not liberty, unity or progress, but inequality, underdevelopment and discord.

The centenary helped usher in a period of conflict and fracture that ended in 1930 with the collapse of the political system and the arrival of Getúlio Vargas, Brazil’s populist dictator. Of course it is important to note how much Brazil has changed since the 1920s: It is more developed, much more democratic, much more equal. But all of these accomplishments are fragile ones, and the echoes between the centennial and bicentennial do seem more than coincidental. As scholars of citizenship and nation building have shown, national holidays are extraordinary occasions, more than simply dates or milestones. They are civic rituals that focus our attention on issues of nationality, of identity, of belonging and exclusion, which we rarely take the time to consider, and therefore encourage contemplation, introspection and debate.

It remains to be seen how far the parallels between 1922 and 2022 will run, whether the current crisis will break the status quo and usher in a new era, for good and ill. In the meantime, it does seem clear that, just as it was 100 years ago, Brazil faces a crisis of legitimacy, and many Brazilians approach the bicentennial as their ancestors did the centennial, not as a celebration but as a moment of pessimism and anxiety, of reflection about why theirs is not the country they wish it to be.

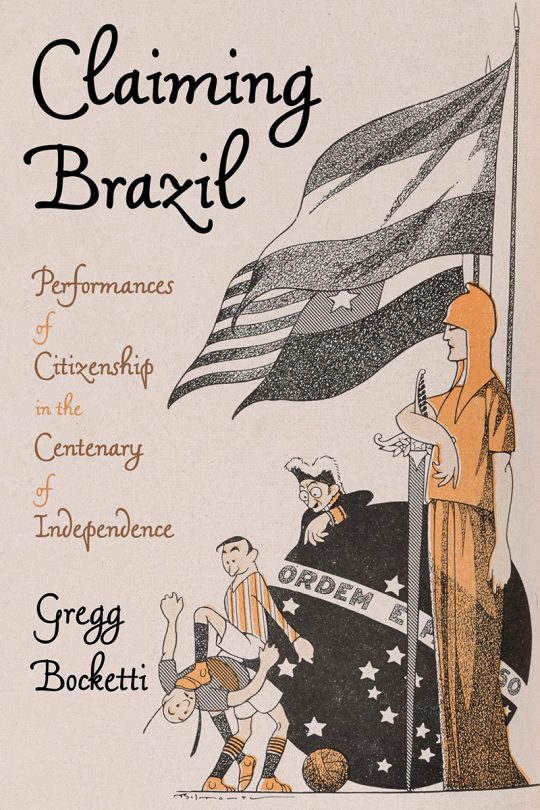

Gregg Bocketti is professor of history at Transylvania University and author of “Claiming Brazil: Performances of Citizenship in the Centenary of Independence,” forthcoming from the University of Pittsburgh Press.