When Sarah Allison ’15 landed her dream job as a public history librarian in Germantown, Ohio, her mentor, Transylvania University history professor Melissa McEuen, asked for permission to brag to the alumni office. She had, after all, pointed Allison to the field of public history. And her former student was now living the life she was meant to lead.

Until her conversations with McEuen, Allison hadn’t known a career was possible in the kind of work that interested her. She’d been thinking about the more traditional route of a Ph.D. until McEuen made the connection for her. “’Sarah, you’re doing it now,’” Allison recalls her mentor saying. “’You work with history, museums and the public side.’”

At the time, Allison muses, “I didn’t know it had a name.” She remembers the conversation as a defining moment. She remains grateful that her professor knew her so well and cared enough to offer direction. “I was always more into the public eye and learning how to teach people at the level they understand rather than at a high academic level,” she notes.

A self-described history nerd from the time she was a girl growing up in the suburbs of Dayton, Allison remembers her early interest in the local history society and a fascination for Mary Todd Lincoln. It’s how she first heard of Transylvania.

As a history major at Transy, Allison had an active co-curricular life. She received a music scholarship as a violist to play in the orchestra. She was a campus photographer, working for the university’s office of communications and the office of diversity and inclusion. She wrote for The Rambler and was a member of the Alpha Omicron Pi sorority, Tau Omega Chapter. She still marvels at the opportunities that an intimate campus afforded her, including the close proximity she enjoyed when notable visitors shared their talents on campus. She especially remembers Peter Bergen, the journalist who interviewed Osama bin Laden, and Sarah Weddington, a Texas representative who argued the case of Roe v. Wade and led to Allison’s unofficial minor in women’s studies.

But it’s the less exalted members of the public who inspire her daily work as a public history librarian and a children’s librarian. Her interests tend toward inspiring a love of reading in children and in doing the work of exploring and safeguarding local history. She’s far more compelled to work to preserve the story and uniform of a lesser-known soldier than, say, Abraham Lincoln’s diary. She knows the Smithsonian will take care of the latter.

For Allison, much of the fun of public history is working with people to connect them to the resources they need. In the history room that she runs in the Germantown Public Library, she recently helped a man track the original ownership of his property back to the Shawnee Tribe. In one of her positions at Wright State University, where she earned an M.A. in public history, she helped a woman who had been searching for a manumission document (a binding document that freed an enslaved person). Allison remembers the response of the woman when she pulled the correct envelope and handed it to her. “She gasped and said, ‘This is it! I’ve looked for this for a decade and it’s been in this folder the whole time.’ These are satisfying and meaningful moments.

“Public history is important,” Allison reflects, “because if the general public doesn’t know their past they’re not going to know how to present it and preserve it for the future.”

Conserving and archiving is expensive work; funds are limited. Part of the challenge of Allison’s work is deciding, within the budget lines for the history room, what is important enough to save. She’s working to make the history room “archivally functioning” for the public, as well as tapping into her previous work as a children’s librarian to create displays and programming for children and their parents.

“Two of my loves have finally come together in one building,” she enthuses. “It’s such a small library that the possibilities are endless.” She’s excited to have the freedom and ability to tackle a range of projects, requiring a Renaissance-woman set of skills, from planning and programming to understanding the psychology of children. She says the skill set comes from her liberal arts education at Transy.

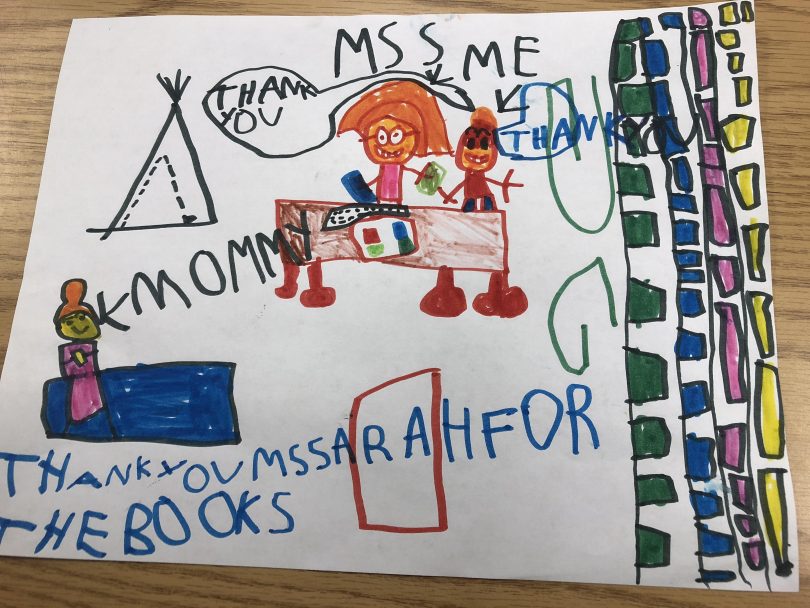

“Some people gauge their job as wealth or as other forms of profit,” she notes, observing that librarians may have a different measure. “My favorite part of being a children’s librarian is that you watch children grow cognitively and see their reading level grow, their interests change.“ She keeps a picture on her fridge that was drawn as a thank you by a young child she mentored. He won an award for summer reading just before entering first grade and was made a library ambassador. “I was so proud,” she says. “I know that if you nurture children and you nurture their reading, they’ll be lifelong readers.”

The similarities with Transy are not lost on Allison, who emulates her alma mater’s nurturing environment, the high expectations and providing the ready resources to accomplish objectives. The democratization of knowledge and resources that she’s part of in her library also inspires her support of her alma mater.

“Transy helped my goals by pushing me beyond where I thought I could do,” she says. “They were always ahead of me. ‘No, you can do a lot better,’” they would tell her. As a result, she was always improving, utilizing the professors, visiting their offices and asking what more she could do.

She remembers how every little gift she received while at Transy helped toward completing her education and the personal transformation that continues to unfold, first as a grad student working on her Master of Library Science at Kent State University, and now as a librarian. Allison is a steady donor to Transylvania. “Though it might not be a $10,000 donation, as from a company,” she says, she understands the cumulative impact of many smaller gifts. But the giving, along with the connection she feels, is something more. It’s gratitude, imagination and a commitment to providing the same experience to others.

“Whenever I give to Transy, I always think of that girl that walked in the first day. She had no idea what four years was going to do to her. And I was definitely not the same girl that walked out on my graduation day as a woman. I can tell you that! So, when I give, I’m sure there’s a girl out there, just like me, that needs my help.”