For Kristin Chilton ’90, becoming the first female chief of the Lexington Fire Department depended on walking two short blocks to the local fire station with the rest of her Transylvania University class. The first aid class, taken as an elective in Chilton’s senior year, presented an opportunity that would alter her future and the course of a community institution.

Before her visit, the business major and sociology minor had been feeling a bit lackluster about her postgraduation job interviews already underway. She’d been wondering how she could make the demanding travel requirements of a sales position jibe with her love of fostering animals. So, Chilton accepted the fire station’s offer to return one night for a “ride along.”

“I was curious about what happens in Lexington at night,” she remembers thinking, “and what kinds of emergencies our local fire department handles.” She had lived most of her life in the city.

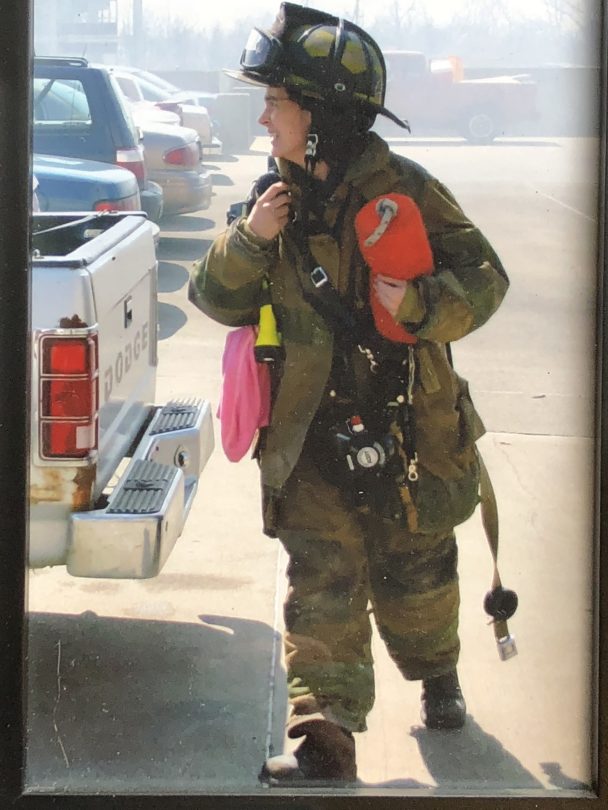

It happened that the paramedic on duty was the first woman firefighter in Fayette County. As the two conversed between emergencies, an idea emerged that fire fighting might be the right career for Chilton. After all, she’d long been working at a local emergency animal clinic, helping animals and their owners during emotional and fraught-ridden experiences. Perhaps it wasn’t too much of a leap to the fire department where Chilton would spend the nearly three decades in service to her community, working her way up to the top leadership role in the department.

Although Chilton can’t remember exactly how she first came to Transy — something about parental guidance and the professor to student ratio — memories of her experiences are crystalline. What she gained in the intimate classrooms significantly influenced her approach to leadership, her goal to diversify the Lexington fire department and her ability to interact with the community. But there were hurdles to jump.

Before Transy, she says, “I was not a really big fan of school.” Having had reading issues as a young child, she tended to derive more information from face-to-face conversation. “I think my parents felt that for me to be successful I needed to be in a small school environment in college,” she adds, “because I was one of those that liked to do 50 other things instead of school work. They felt that I would be more engaged in a program like Transy’s versus a school where I could be one kid in hundreds in a hall getting a lecture.”

In fact, Chilton traces her development as a leader to that personalized attention and the demands of a smaller class size, including the mentoring, participation and being able to engage with a variety of perspectives.

“I remember taking a sociology class and studying tribes halfway around the world. I remember being really interested in how different people lived and what they found important in their society. It’s just being exposed to things that I wasn’t exposed to in high school,” she says. And she found herself wanting to learn more in that class, sitting around a table with five other students and the professor. “That’s how small and intimate the class was. I just remember there being a great group of people and great conversations about things that you wouldn’t get in a large school environment. That’s what makes Transy so unique — that closeness of the campus feel and the value that I felt from the professors.

“Professors were so involved and took such an interest in their students,” she continues. They mentored and motivated you to be the best that you could be.” Leadership skills and confidence began to emerge. “You got more opportunities in the classroom to speak or to be involved or ask questions or work on projects,” she recalls. “It sets that stage early in your mind that you matter, you’re important and you can be a valuable member.” That sense of being valued extended to valuing others in the community.

Whenever Chilton is asked about the benefits of a college education, she immediately focuses on the exposure to other people and ideas. The experience offered her a community of insights and backgrounds different from the familiar circle of friends she’d known since childhood. “Hearing their stories, being in the same class and communicating with each other,” she insists, was important as well as interesting. “I think it really opens your views of other people in the world.”

Having access to new perspectives later helped Chilton to visualize a more inclusive institution. It fed directly into her core tenet as chief to make a diverse and inclusive fire department. Diversity, she points out, brings greater community representation, but also a stronger set of skills and abilities that help to form a more complete team. As a woman coming up through the ranks of the department, she remembers “awesome mentors,” she says, but also many objections and obstacles for simply being female. Those pushing against her progress may have riled her tenacity to work even harder to succeed, but they also made her understand the absolute necessity of making people, who may be different or unfamiliar to the majority, feel welcomed.

Therefore, Chilton has been committed to bringing people into the fire service who, like herself, might never have considered the career if the possibility hadn’t been presented. That requires dispelling some misperceptions.

“When you look into all the areas of the fire service and the different things we do, it’s a team effort,” she explains. “It does take the big guy, but it might also take someone small and petite to get down into a small opening or into a confined space. And in an emergency situation, she adds, “someone might be more comfortable relating to someone who looks and sounds like them. So, it’s very important for us to bring all of those people together on a team, because a team is going to be more successful when we go out in the community. It’s been really important to me to make that a goal for us to go out and reach those individuals.”

Breaking down barriers within her staff and fire fighters has been part of the process, too. She’s worked to help them see their common humanity and shared goals. “The problem is that we’re just not familiar,” she says, drawing from her experience at Transy. “If you’ve never been exposed to someone who is different from you, it makes you uneasy and uncomfortable. But once you break down that initial barrier, then you realize you’re not that different. You’re just uncomfortable with something you’ve not been exposed to.”

Given the breadth of what the fire and emergency services handle, there must be a job for every skill set. When Chilton started her career, the work was largely fire and EMS, with just the beginning of hazmat operations. Now special operations extend to many types of rescue: from large animal and confined space rescue to swift water rescue. Firefighters are trained for terrorist attacks as well as active shooter and active aggressive scenarios.

“It’s always changing,” she says of a department that has grown in size and resources, with increasingly specialized trucks and equipment. “Technology has been one of the biggest changes since I joined,” she adds. “The fire service continues to take on tasks that nobody else can or is willing to handle. We rescue animals, put flags up on flagpoles. We do presentations at schools and lots of things people don’t even realize.”

As a leader of the department, Chilton has given particular attention to people, not just the apparatus. “You have to lead as a whole for the organization,” she explains, “but there are instances when you have to look at the individual. I think one of the most important things is caring about people and taking care of them.” She relies on the entire organization to accomplish that level of care. “Making sure that we can do that is very important to me.”

A similar motivation brought her to the decision to retire. One of the greatest challenges of being chief has been the time commitment. “You can’t be everywhere all the time,” she says, nor can you be all things to all 625 employees. It has bothered her that she couldn’t attend every visitation or hospital visit or wedding. But even harder, perhaps, has been managing the work-life balance. “My family, I’ll be honest, has sacrificed. It was a family sacrifice for me to do this.” She’s looking forward to undivided time with her 13 year-old daughter, her husband, a retired firefighter, and their many foster animals.

Perhaps she’ll even have time to look back on the full scale of her career, as she once did after answering emergency calls. “It’s after the run is over,” she remembers, “that you sit back and evaluate what happened, what you did and what you saw. That’s when you feel the full effect of it. You don’t think that much going into it — how dangerous it could have been. You’re running on adrenaline at that point. You’re getting on the truck, you’re getting off, and you’re doing what you’re trained to do. But you’re not really evaluating it until after it’s all done.”