Certain sounds and phrases echo in the ear for life, usually because they hold some deeper meaning.

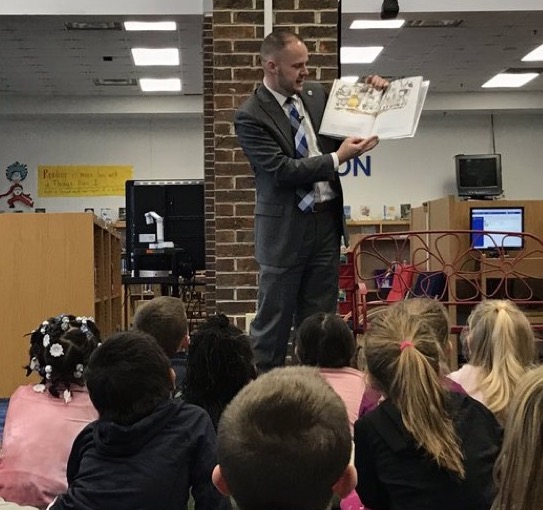

Kevin Brown ’97 remembers the sound of his principal walking down the wooden floors of Paint Lick Elementary in Garrard County, Kentucky. It made him sit up straight, he recalls, not out of fear, but respect. She offered reassurance during times of setback and built up confidence in his abilities.

Brown experienced early on the importance of having the right leader in place to answer the needs of Kentucky’s children.

That education should become the focal point for Brown’s interest in public service is only natural. He grew up listening to conversations at the dinner table between his mother, a second grade teacher, and his father, a longtime member of the local school board.

A defining moment for him came in fourth or fifth grade when he accompanied his father to a contentious school board meeting over the closure of a deteriorating elementary school. He can still hear the screams of irate parents in the gym and feel his own amazement as the board made the unpopular decision to vote against the wishes of the impassioned parents for the greater good of the entire county. It was his first taste of politics and policy making.

“From then on I was interested in public service,” says Brown, who earned a degree from Transylvania, majoring in business administration and minoring in political science, before pursuing his law degree at the University of Kentucky. He joined the Office of the Attorney General, where he first demonstrated his strengths in handling cases dealing with education policy. His path was set.

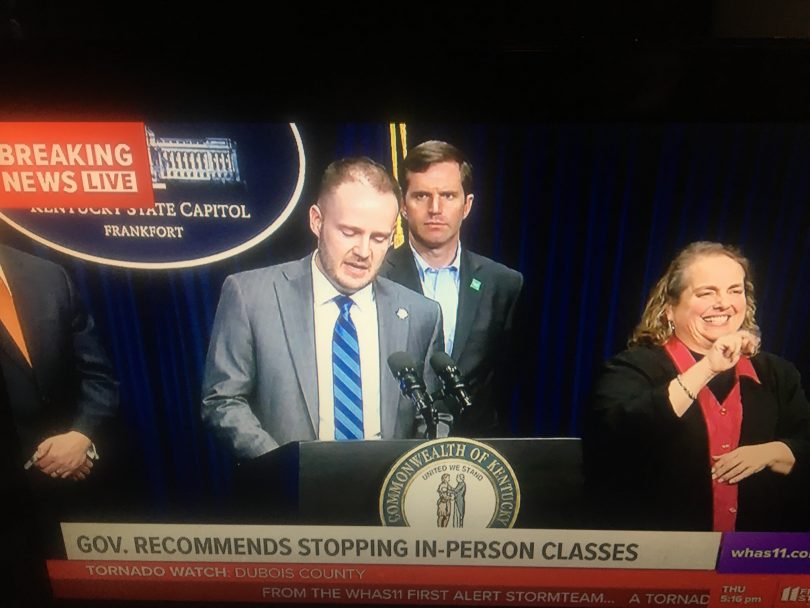

In December of 2019, Brown was asked to take temporary leave of his position as general counsel for Jefferson County Public Schools and the Jefferson County Board of Education in Louisville, Kentucky, in order to serve as interim commissioner for Kentucky’s Department of Education. His goal, having served in this capacity before, was to keep the system running smoothly until the new commissioner arrived some months later.

Then came the novel coronavirus. In March of 2020, almost overnight, school districts were required to shutter all buildings and replace in-class learning with online instruction. “There was no guidebook,” Brown says. For all of the premade emergency plans, nothing accounted for a COVID-19 scenario.

“I can remember thinking to myself, driving to work or lying in bed at night,” Brown recalls, “‘what are the things we need to focus on during this pandemic?’ The three words that came to my mind at the time were educate, feed and fund. We later changed that to educate, feed and support.”

Of the 171 districts, only 83 had any experience with nontraditional instruction (NTI), and it had usually been limited to a snow day or a week at most. Yet, within 48 hours, full-scale NTI learning plans were submitted. The necessary technology was already in place at every school in the state. All systems might have been “go” if not for the monumental, pre-pandemic challenges already facing educators.

Even in 2018-19, nearly 400,000 public school children in Kentucky were considered economically disadvantaged. Children need nutrition and emotional support before the teaching can begin. Meeting those needs is difficult on the best of days.

“We still don’t reach every child, even if that child is sitting in a classroom,” Brown explains. “Students bring with them the trauma they have endured in their lives or endure on a daily basis because of home situations and things they experience. And that’s just in a normal time in our society, let alone the things we’re going through now and the unrest. That’s a struggle the education system deals with on a daily basis.”

What happens, then, when a pandemic dismantles the delivery systems in place — the two nutritious meals per day, access to a school nurse, emotional support and the special education programs? “It’s hard for students and families when we’re out of school even for one snow day.” But for weeks and months on end? Brown could visualize all of these issues compounding.

So, he and his team consolidated the focus, shifting from meeting long-term goals, like reducing the achievement gap, to finding ways to meet the basic needs, for example, by pivoting bus drivers to help with the delivery of food.

“The basics for us at the state level were to provide a mechanism for districts to provide some form of education and food to children,” Brown explains. “We were going to do everything in our power at the state level, working with the General Assembly and other partners, to ensure that state funds continued to flow during this time to make sure districts could continue to educate and feed students.”

Brown recalls the many moving stories of how districts delivered food and materials, going door to door, communicating through windows to check on special needs students while maintaining social distancing. “The fact that our teachers, principals and staff were dedicated to it, made the job a lot easier,” he says. Brown consistently credits the quality and shared purpose of educators, administrators and his leadership team.

“We knew that we had to deliver for Kentucky’s kids. We had to be a rock that school districts could rely on, to give them constant feedback, support and guidance. We communicated with school districts weekly through webinars and webcasts. There are hundreds of webcasts, now archived between the months of March through July, and they’re still going on.”

When Brown and his team set up an emergency operations type of “war room,” they knew that communication would be essential in getting through the initial stages of the pandemic.

“You cannot over-communicate, particularly during a crisis,” Brown says. Providing information was invaluable because it was evolving every day. “This was a scary time for parents,” he adds. By communicating with families regularly through his digital letters, the department also reinforced the efforts of local districts to explain everything from logistics to the health department’s guidance on masks.

Reading through the letters offers a snapshot of the times and another reminder of how the education system absorbs all of the issues and complexities facing American society. Brown didn’t shy away from addressing them directly. In his letter of July 10, he recognized the persistence of racial inequity in the school system, appealing to readers to bear in mind that “Kentucky’s society and its economy cannot be or remain healthy if we are leaving a significant portion of our students behind.”

An open, empathetic and effective leader, Brown draws a direct correlation between his ability to navigate the journey of unknowns and his liberal arts education at Transylvania.

Brown, a William T. Young scholar at Transy, spent one May term in Costa Rica and another in Egypt (left). With the help of professors and staff, he was able to realize his dream of interning and working in politics in Washington, D.C., before entering law school.

“You have to be able to pivot. You have to be able to synthesize the information,” he explains. “These types of skills are actually in keeping with what Transy does. That’s the beauty of a liberal arts education — to synthesize information, to be able to problem-solve and apply knowledge to a unique situation. That’s what Transy is all about. They don’t give you a bucket of knowledge, they give you the ability to tackle that bucket of knowledge the rest of your life.”

They don’t give you a bucket of knowledge, they give you the ability to tackle that bucket of knowledge the rest of your life.

When the Kentucky Association of School Administrators recognized Brown’s efforts by presenting him with the 2020 William T. Nallia Award — given annually “to an education leader who reflects a spirit of innovation and cutting-edge leadership while bringing higher levels of success to all children — the executive director stated that Brown was “the right person at the right time.”

But Brown quickly deflects the idea that he alone was responsible, hearkening back to the leadership modeled by his grade school principal and the college experience that helped shape him and his methods.

“Critical thinking,” he says, “doesn’t mean sitting at the department with my Transy degree coming up with all of these solutions. It’s being in a position to enable the team around me to do that.” His approach to having a “united, purpose-driven team,” he says, “is also in keeping with the liberal arts — to work together as teams, to rely on other information and to rely on valuable pushback.” Wanting to know the flaws in his own argument is right out of Transy, he notes.

“I can hear Dr. Dugi [professor of political science] right now talking about acting in good faith,” Brown says. “That’s a principle he ingrained in us at Transy, and one of the things I keep coming back to. I think that was his way of saying that our society, in many ways, is dependent on everyone acting in good faith.”

Brown still takes to heart the responsibility of being a William T. Young scholar. That investment in him, which made his Transy education possible, also inspires him to give back to Kentucky. “I took that charge seriously,” he says, “and believe it is a way to pay the debt back to Mr. Young and Transy.”

Back in his job as general counsel, and looking ahead, Brown can see how important a liberal arts education will be in our ability to deal with the many monumental issues of our day, including equitable education, climate change, social and economic justice and how we interact with one another.

“All of those things going on at once,” he says, “call for solutions by creative thinkers, critical thinkers and, in my opinion, liberal arts graduates. I relied upon that heavily and am thankful for it every day.”