Amid the racket that accompanies our social isolation — the noise of fear, the hissing of uncertainty and the whining of impatience — a single poem can lift us wholly into another dimension. We become one with a singular story, rapt by its music and revelation. We shape our own meaning in the space between the lines. We connect to our humanity.

Maurice Manning, a Transylvania University English professor and writer-in-residence, recently shared five poems written during the current shutdown as part of “A New Decameron,” an online project inspired by a 14th-century response to the plague. The collection of diverting stories, written by Giovanni Boccaccio in 1348, endeavored to entertain and reassure his community.

“Boccaccio’s idea was to recognize we’re all compelled by story,” says Manning, agreeing with that notion. “In trying times the stories we tell are a comfort.” The process brings its own salve to the writer, too, as Manning describes how much he enjoyed “allowing myself the freedom to think and to be beyond our present moment.”

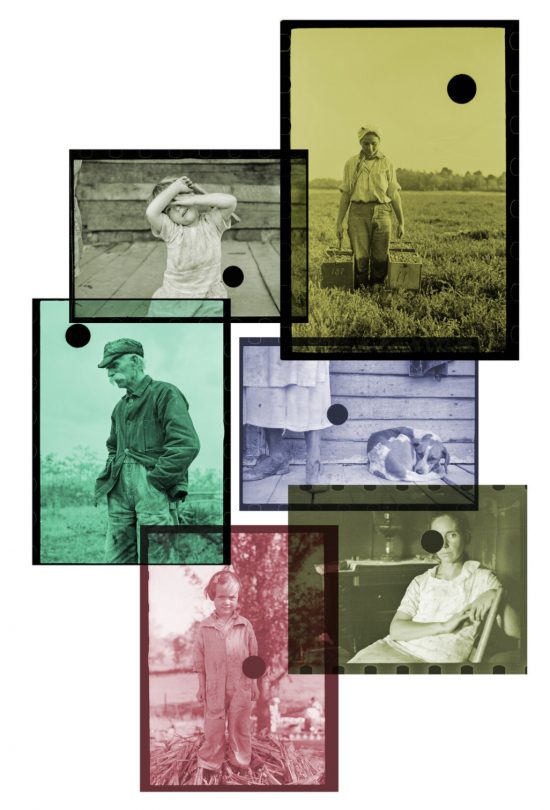

The online project offers photographs and an audio reading of each poem. Manning’s contributions include imaginative celebrations of his ancestors in Clay County. The poems show how curiosity, memory, imagination and art combine to create transportive experiences and multidimensional, connective stories that bring us closer to each other. They are, he notes, “simply ones I thought would address the purpose of the ‘New Decameron’ project: to entertain, to offer hope, to lighten the load.”

Read and listen to Manning’s poems.

Q&A with professor Manning

How did you become involved in this project? What inspired you to participate in it?

I became involved in “A New Decameron” because I got an email from one of the organizers, Pete Candler, a photographer, filmmaker and writer based in Asheville, North Carolina. Boccaccio’s original effort was to share stories high and low during a plague year back in 1348, to bring comfort and entertainment to people who were suffering and uncertain.

Just before our shutdown, I was often spending time in the genealogy room of the Boyle County Public Library, because our daughter was in preschool in Danville, and I had a couple of hours on my hands and the room was the quietest place in the library. One day, about a week before the shutdown, I spied a book on the shelf: “Pioneer Families of Clay County, Kentucky,” published in a local, nonprofessional manner in 1970. The book includes mention of my father’s people and his mother’s people. There are great names attached to stories I grew up hearing, and the stories go back to the 19th century and before. This sense of history and the knowledge of belonging to it is a wisdom I have long pondered and enjoyed.

All of the poems I’ve shared for the “A New Decameron” project have been written in the shutdown but have not been written in any response to it. Instead, I’ve enjoyed allowing myself the freedom to think and to be beyond our present moment. I’ve enjoyed that opportunity immensely.

The project’s call is for stories about humanity that address our existence in this era of coronavirus, but without mentioning anything to do with the virus. Why do you think poetry is such a perfect medium to accomplish this?

I think poetry or creativity in general can offer a relief from the burdens of the moment. That is not to trivialize the severity of our present concerns — it simply is a sign that we must continue to be human and humane, and we have to live with hope. As we miss each other and being in company, we have to find creative ways to be together. That’s what I so enjoy about Pete’s project. It’s a way to keep going, and that’s what we have to do.

What was your process for selecting the poems?

I did not write any of these poems as a response to Pete’s invitation. I simply hit a bit of a writing stride just before our shutdown. At some point in the last few weeks I began to wonder if our ancestors imagined future generations and if they made provisions for later generations. I think they must have, and pondering that has been moving to me. I know this is the case with some of my ancestors. I have felt an intense connection to my ancestors, and the poems I’ve been writing the last few weeks are an effort to honor them, some of whom I knew and loved, and many I only heard about.

I loved having the audio version as a chaser to my silent reading of each poem, not simply because the music of the language deserves to be heard, but because it felt like storytelling. And it brought out new meanings for me. Can you tell me something about the value of you, the poet, reading your poetry aloud to the rest of us and what you think about as you approach a poem for reading aloud.

I often tell my students that poetry is halfway between thinking and singing. It’s a kind of “talk,” which requires it to have a listenable quality. A simpler way to say this is poetry comes to us from an oral tradition, from the ancient human experience of sitting around the fire or the hearth and telling stories to each other. It must be one of our oldest efforts to belong to each other.