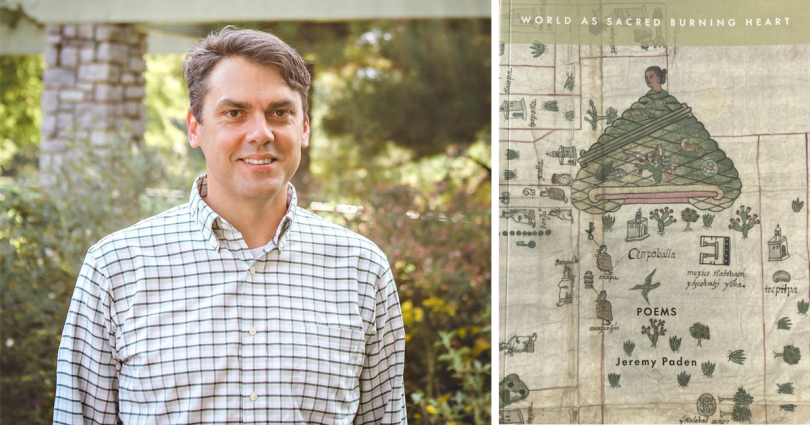

For April’s National Poetry Month, Kentucky Humanities interviewed Transylvania University Spanish professor Jeremy Paden on his “World As Sacred Burning Heart” book of historical poetry. The discussion is part of the Think Humanities podcast “for people who love history, philosophy, culture, literature, civic dialogue and the arts.”

Listen to the program:

Professor Paden shares the story behind these poems below.

For the last six or seven years, I’ve had a folder anchored in my master archive titled “Captain Poems.” It contained all the many poems about colonial Latin America that I had written starting in the early 2000s. On April 6, 2021, I received a box of books from my publisher 3: A Taos Press. It was the author’s copies of “World as Sacred Burning Heart,” a lyrical meditation on the first century of the European conquest of the Americas. Andrea Watson, the publisher, Debra Kang Dean, a fine poet from Indiana, and I had spent the first half of the pandemic ordering and editing all those colonial Latin American poems into a coherent collection.

The spark for the collection came in the mid-2000s when I wrote a poem on a quipu — an Inca mnemonic device. It was published in 2009. I had tinkered with the poem for a while, but before I sent it off for publication I asked Martha Gehringer to read over it, and she helped me make some edits. In fact, many of the poems in the collection were read first by professor Gehringer. She has been so instrumental in my own writing life that I dedicated the book to her and to my Colonial Latin American professor at Emory, Karen Stolley. Over the following years, I slowly built up the collection.

The three principal strands of poems are:

- Prose poems about captains like Columbus, Cortés and Las Casas. These poems play with the language and syntax of 16th-century chronicles and use irony to interrogate the official story.

- Ekphrastic poems on maps, quipus, Aztec featherwork mosaics and other cultural objects.

- Poems of resistance.

The “Captain Poems” are not quite persona poems — they are all written in the third person rather than the first. But one way to think about them is as if they were persona poems or a kind of dramatic monologue (or at least as if they rely on the ventriloquism of the persona poem). Two such works I remember from college are Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” and “Fra Lippo Lippi.” These are not his only examples, but both use dramatic irony and voice in masterful ways. Frank X Walker provides another example of a poet who deftly writes persona poems. Specific examples from among his many books are the “York” poems from “Buffalo Dance: The Journey of York” and “When Winter Come: The Ascension of York,” as well as his book “Turn Me Loose: The Unghosting of Medgar Evers” on the murder of civil rights activist Medgar Evers.

When writing the prose poems, I went back and forth between keeping them as the prose poems that they are (and were originally conceived to be) or putting them into something like the octava real, the stanzaic form for 16th- and 17th-century epic verse in Spanish. In fact, one of professor Maurice Manning’s recommendations was that I try to wrestle them into a more traditional form. But the language and syntax these poems drew from were the journals, letters and histories of Christopher Columbus, Ramón Pané, Hernando Cortés, Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo, Bartolomé de Las Casas and other conquistadors. And they just kept insisting on being prose.

As to the voice, or person, most persona poems speak in the voice of the character. That is, the first person. The “Captain Poems,” however, are mostly in the third person, though they occasionally move between the third and first person. This decision was also guided by historical examples, albeit nonpoetic ones. Namely, Caesar’s “Commentaries on the Gallic War and the Civil War” and the formal aspects of Columbus’ ship log helped convince me not only to keep the in prose but to keep an ambiguous play between the first and the third person. In the case of Caesar’s text, he writes of his campaigns in the third person. In the case of Columbus, the extant diary or ship log has come down to us through Las Casas, where the first and the third person point of view mix and mingle.

In the end, this is a collection of poems that tries to study the various ways in which power justifies itself to itself even while those very justifications unwittingly confess to having committed a variety of atrocities.