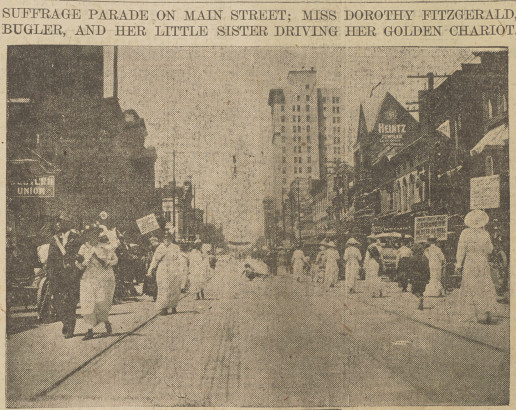

Just across Third Street from Transylvania University, some faculty members joined a crowd gathering for what was to become the largest suffrage parade in Kentucky history.

These marchers making their voices heard on that spring day in 1916, along with others like them throughout the nation, helped pave the way for the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote. Its adoption was certified Aug. 26, 1920 — an anniversary we remember on today’s Women’s Equality Day.

A Lexington Herald article describes the 1916 marchers, who after assembling in Gratz Park turned onto Broadway and made their way to Main Street. “Flaunting their ‘Votes for Women’ banners and their yellow colors and with the strains of two big brass bands filling the surcharged atmosphere, the suffragists of Lexington and central Kentucky, with their friends and sympathizers, marched through the streets of Lexington … lined with thousands of spectators.”

Besides the marchers, many wearing the white clothes symbolic of the movement, the parade included floats, horses and automobiles bringing up the rear. Onlookers cheered as they passed.

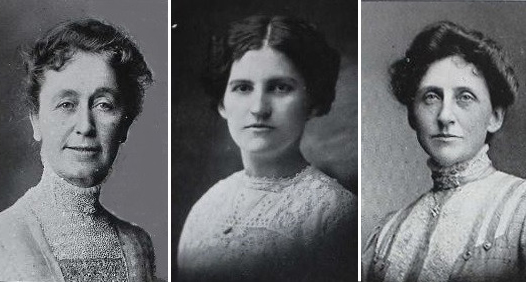

According to the H-Kentucky network’s Kentucky Woman Suffrage Project, among the marchers were Transylvania math professor Alice Tribble Karr. Four years later, she became dean of women for Hamilton College, which had merged with Transylvania around the turn of the century.

Hamilton’s director of expression and dramatic art, Julia Woodworth Connelly, also participated. “She was involved in the civic life of Lexington, including the Woman’s Club of Central Kentucky,” according to an H-Kentucky blog posted by historian Randolph Hollingsworth.

A delegation of 54 women from Hamilton signed up to participate in the parade, including President Ida V. Thomson and piano professor Sarah McGarvey.

Transylvania history professor Melissa McEuen, co-author of “Kentucky Women: Their Lives and Times,” said these Lexington women who were devoted to suffrage weren’t one-issue activists. “They recognized the connections between voting rights, educational opportunities, public health and numerous other social and economic issues. And they were tireless in their campaigns to bring about change. They didn’t always agree on methods or who should be included in their deliberations, but they were confident that women’s voices and votes could challenge an increasingly violent and corrupt political culture that disgusted them.”

McEuen also noted how “Hamilton College professors — who taught female students segregated from their male counterparts at Transylvania — were among the many Kentucky women who supported and helped to shape a national conversation on political equality.”

In another H-Kentucky blog post, Hollingsworth wonders about the origins of the “unique grouping of women’s rights activists” at Transylvania and the newly merged Hamilton — “Perhaps it was the charisma of the vision that the new president, Burris Jenkins, had for a rejuvenated Transylvania College soon after he arrived in 1901. Perhaps it was the long tradition of Lexington’s support for women’s professional education and higher learning.”