During the early days of the coronavirus shutdown, Transylvania alumna and visual artist Annelisa Hermosilla needed a project and connection. She’d recently finished her collaborative work illustrating “Under the Ocelot Sun” with Jeremy Paden, a poet and Transylvania Spanish professor.

Looking around her house in Virginia, she spied a lifeless hoodie, that ubiquitous swathe of quarantine couture. She set to work re-imaging it as a canvas and posting the image on Instagram with an invitation to her followers. In no time, friends and family began to ask for hoodies and T-shirts of their own, and a singular business — and connection — was born.

Hermosilla, who graduated in 2018, was happy to oblige the requests, in part because her art is about relationships. She is drawn to exploring the interactions between people, things, memories and emotions, and the meanings within them. In the process, she’s learned how interpretations are as distinctive as the beholder of the art. In the case of the hoodies, the artwork became her take on the person ordering the hoodie, rather than just a surface representation of them.

“What inspires me,” she explains, “is my perception of that person and how I know them — my experience with them and how they seem to me. That’s what I create.” She takes time to talk (virtually) with each person who places an order. Most give her free rein.

That sense of people’s trust in her creativity began at an early age. Hermosilla’s mother, who has actively encouraged her art from the time of her first painting in kindergarten, gave Hermosilla creative license to draw on the walls at home. Never a reckless or idly scribbling child, she recalls, “I was serious.” She would plan, draw and then fill in the images with color.

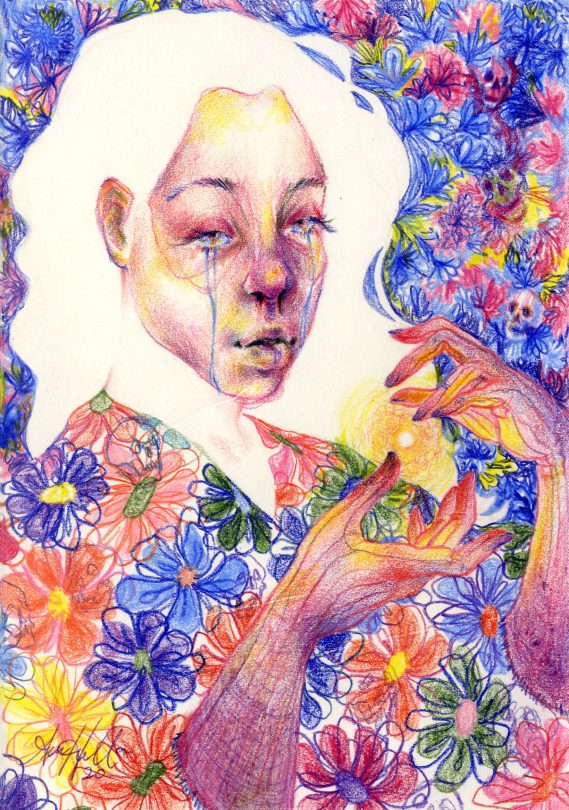

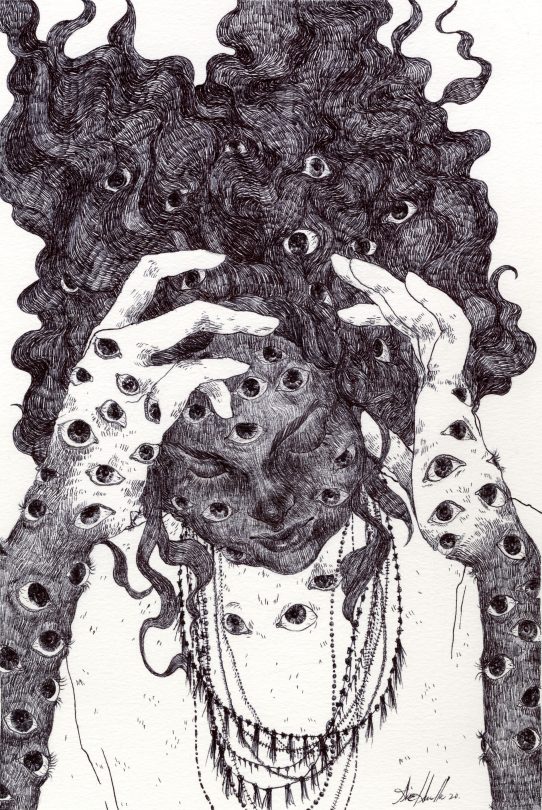

“Ojitos” — yellow hoodie that Hermosilla made for herself

“Acid Face” — maroon hoodie (commission)

“Frenchie Vibin’” — blue hoodie (commission)

Growing up in Panama, she remembers drawing cartoons that she saw on television and interpreting what she read in books. As a junior in high school, she illustrated a cover for an e-book. But it wasn’t until 12th grade, when she sold her first artwork, that “something clicked.”

She describes the pencil drawing she’d made of her cousin’s eye, “in perspective with a reflection from the window,” to which she added watercolor and color pencil. “It looked really interesting,” she remembers. “I drew it for fun.” Then a friend of the family wanted to buy it as a gift for her father, an eye doctor, to put in his office. In that moment Hermosilla remembers thinking, “Oh, I can actually do something with this. Someone actually likes my work. They trust a 17-year-old to make them a picture. So maybe I could run with this.”

Her high school guidance counselor recommended pursuing her art in the United States and at Transylvania, in particular. She arrived at Transy with a “very narrow idea of art,” she says. Her professors helped her out of that mindset.

“I definitely grew a lot. My professors pushed me to be better, to not just think of art as hyper-realistic or in an academic sense, but to expand beyond that to see that art is supposed to be accessible to people who are not in academia, who are not in museums or galleries — that art is for everybody.”

Hermosilla notes how a broad liberal arts curriculum — especially psychology, sociology and anthropology classes and the study of society and social issues — helped her art grow. “Now I think my art has a lot more meaning in it. I’m able to convey my thoughts a lot better than simply making something for aesthetic purposes.” Added to this were art history classes that, she says, helped to clarify her role as a creative person and the relationship between the artist, the artwork and the audience.

“I realized that it’s very difficult to separate art from the artist and the artist’s experiences,” she explains. “Understanding that made me realize in my own practice that I’m not just creating something, but that everything I make has a purpose and a meaning.” Much of her art, for example, focuses on women and draws on religious influences and her Latin heritage. “I thought I did that just because,” she says. But taking the classes highlighted those underlying themes. “They made me realize that the reason why I paint these things is because I’m living through certain issues that exist in textbooks or what we talk about in the news.”

For Hermosilla, art provides the perfect medium for expressing and communicating. It is, she says, “an extension of me and a more articulated version of my thoughts.” Where language may fail her, art successfully conveys the complexity and depth of what is inside her. And the process of creating reveals unexpected connections.

“Art really serves as a tool and a pathway to touch on internal conflicts and thoughts, feelings and emotions that you may not have thought of before,” she explains, “because you start off with a picture and then it starts evolving, because the color triggered something in your memory or the shape that you made calls up a nostalgic memory in your head, and you’re like, ‘Oh, where did that come from?’ So I think that’s why I say that art is important as a tool of communication.”

In that communication is the ultimate collaboration. As she learned at Transy, in that moment when art is shared with the community, its meaning no longer belongs to the artist, but to the audience members and their interpretation. It’s that active give and take between artist and audience, and seeing the impact of her work — as she has with the publication of “Under the Ocelot Sun” — that has solidified her desire to continue. It’s confirmed, Hermosilla says, “that I’m really on the right path.”