Dr. Gerald “Jerry” Grant ’81 jokes that the trajectory of his impressive career path is due, in part, to a bit of attention deficit disorder. He gets bored easily.

It’s why the Transylvania University graduate didn’t stick to his original plan to open a practice in general dentistry after graduating from dental school at the University of Louisville. And it’s why he wasn’t content with specializing in prosthodontics after he joined the Navy. Making crowns and bridges, implants and full-mouth reconstructions simply wasn’t enough.

“I wanted something more exciting,” he says with laughter.

So, Grant took on maxillofacial prosthetics, a subspecialty of prosthodontics, which provided ongoing challenges in the rehabilitation of patients with head trauma. The most challenging reconstruction cases for cranial plates, he says, involve the eye or part of the face. He describes sculpting ears and noses, developing plans for implants, and the quest to improve upon the conventional way of creating cranial plates for injured active service personnel. He remembers how the old way required making an impression of the patient’s head, figuring out the size and then going into the operating room to “grind on until it fits.”

In the late 1990s, he became fascinated by digital imaging. “We started looking at it for fabricating cranial plates,” he recalls, noting how having prints from a CT scan improved the fit of the plate because he and his colleagues could make it “directly on what the skull would be.”

After Sept. 11, 2001, when he returned to what would become the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, the quantity of head and neck injuries demanded the development and application of these new technologies. From 2004-15, Grant and a team from Walter Reed Army Medical Center and the Naval Medical Center Bethesda built up the 3D Medical Applications Center — “the first one in a hospital of that magnitude,” he adds. When the two facilities merged as Walter Reed National Military Center in 2010, he was selected as service chief.

They printed in resins, plastics, powder and titanium. And because they were online, they could reach active duty personnel anywhere in the world, getting images, building devices and surgical guides and then sending them out. “We could send things to Kandahar, Afghanistan — it didn’t matter where,” he says. “As long as the post office went there, we could send it.”

When asked about the results of these efforts and the differences made to the lives of the service members, he emphasizes the techniques developed by the team as he recalls the outcomes.

“I couldn’t have done that without the techniques we’d developed to do it,” he says. “We had patients that actually were nonambulatory — you couldn’t move them.” After getting a cranial plate, “they were sitting up and talking — and they hadn’t done that in six months. So those are the kind of things that you see and realize, I guess it does work.”

Every case is something different, so you never seem to do the same thing twice.

Dr. Jerry Grant

On a different scale, but also essential to the quality of the long lives ahead for so many young service people, Grant’s department created a range of useful accessories for quality of life.

“We did a lot of making things for patients missing limbs. One of the things you don’t think about is, if you have a hook, how do you hold a beer mug or wine glass? Or if the guy likes going fishing, how do you hold a fishing pole? So we developed a whole lot of stuff that’s customized for people who have those types of prostheses.” Because they’re all active, he adds. “We even built skates for someone missing both legs so that they could skate and play hockey.”

While working in maxillofacial prosthetics, Grant notes, it was a constant, evolving form of problem-solving. “You take what you’ve known from before and you have to apply it to something the rules don’t apply to anymore,” he explains. “Every case is something different, so you never seem to do the same thing twice.”

By the time he retired from the Navy in 2015, where he’d been teaching research in the dental school as well as heading the 3D modeling in the radiology department, he was a veteran of imaging, design and production, collaborating between disciplines and all the many elements that go into customized reconstruction.

“My success in the military was because I could think through systems,” he explains. “I could think in steps and I could think through a problem.” It’s part of what he learned as an undergraduate at Transylvania. “You have to visualize what’s going to happen in the end and then figure out what the steps are going to be to get to that end point.”

Grant jokes that he “wasn’t the most brilliant student at Transy. It was a tough school.” But the 2016 recipient of Transylvania’s Distinguished Achievement Award acknowledges the foundation he built, the way of thinking and the interdisciplinary grounding offered by the liberal arts.

“The teaching environment at Transy was perfect for me,” he explains. “It wasn’t me memorizing a bunch of stuff; it was learning systems and learning how to think through something. I think that’s what I got. Because of the smaller classes, it was easier to ask questions and make you think about what you’re doing instead of just spitting out data.”

A civilian since 2015, Grant continues as a consultant for the 4D Bio3 military bio-fabrication project that he helped to launch before he retired from the Navy. Current projects include the blood-brain barrier studies and the reconstituting and reprinting of blood.

But his daily challenges involve the development of “medical and dental devices for customized care” — some of which are vitally pressing — through interdisciplinary collaboration at the University of Louisville. He serves as a professor and interim assistant dean of advanced technologies and innovation at the School of Dentistry and associate director at the Additive Manufacturing Institute of Science and Technology.

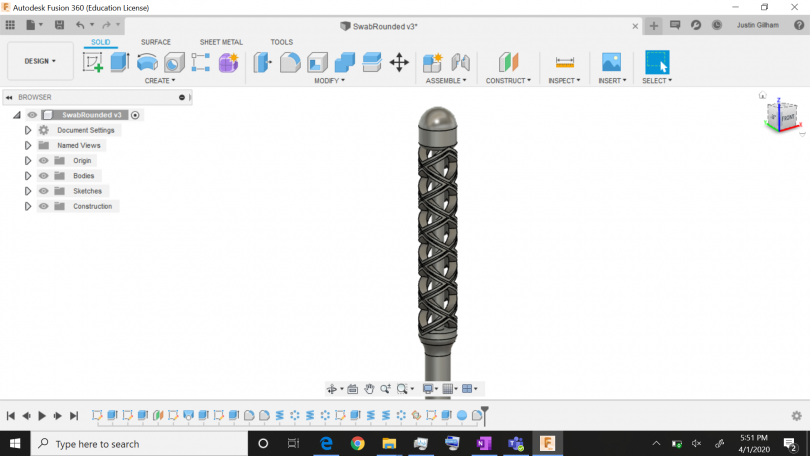

Most recently, Grant and the team of innovators have been in the news for responding to the urgent need for COVID-19 testing by creating a 3D-printed testing swab that can be reprinted as needed for use throughout the Commonwealth. Previously, they devised face shields, again at the behest of the state for application during the coronavirus. The next goal is to better understand aerosols in the context of getting health clinics, particularly the dental school, back up and running safely. Grant, a past president of the American Academy of Maxillofacial Prosthetics, is already visualizing the end point and the steps to get there.

Every day presents a new challenge. Being bored is not an issue.