Jumping aboard a ship bound for Liverpool, England, in the mid-1960s, Herb Ressing had no master plan, no blueprint for life. He only knew that he wasn’t yet ready to settle down and study. So, the native of Buffalo, New York, left his Transy Class of 1966 after freshman year and found himself in the bowels of a ship churning across the Atlantic. He couldn’t know that one day, after a career on Capitol Hill, he would be sailing the seas again after buying legendary anchorman Walter Cronkite’s yacht.

“Vietnam was cooking,” he recalls. When his father, long frustrated by Ressing’s pattern of enjoying life and neglecting his grades, suggested he go to Vietnam in order to grow up, he looked at his modest funds saved from part-time work and replied, “No, I’m going to go to Europe.”

He worked as a chauffeur in Scotland, at an import/export firm in London, a plastics factory in Paris and a BMW factory in Germany. He took the train from Vienna to Prague and on to Moscow. But after a year, he says, “the draft board was getting hungry. That was a motivator to get back to college.” This time would be different, but also very much the same. As his memories reveal, more than 50 years after returning to Transy to finish his degree, Ressing could be talking about Transy in 2020. The core experience remains; it’s the person who evolves.

“The thing that struck me about Transy,” he says, “the classes were small, the relationships with professors were big; it was not just in the classroom, it was everywhere. When I think back … the intimacy of the relationship between students and faculty was very, very appealing. That’s a big plus.”

He singles out the guidance of professors Joe Binford (history), Tom Cutshaw (political science) and Bill Thompson (theater): their academic support, the friendships formed around the dinner table in faculty homes, opportunities identified and rules reinterpreted to ensure that his year away would not impede his progress.

“Professors were very helpful in guiding my thinking. I was a loose cannon,” he chuckles. “I would go over to Joe Binford’s house and his wife would cook us dinner. We’d sit around and chat about everything. That kind of relationship opened up a lot of doors that I wouldn’t have been able to open had I not had it,” he reflects on the confidence it built in him and his ability to succeed in Washington.

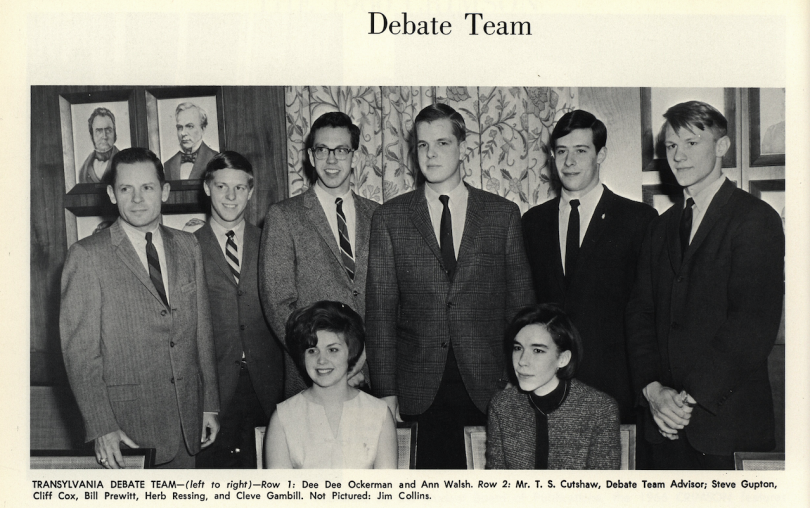

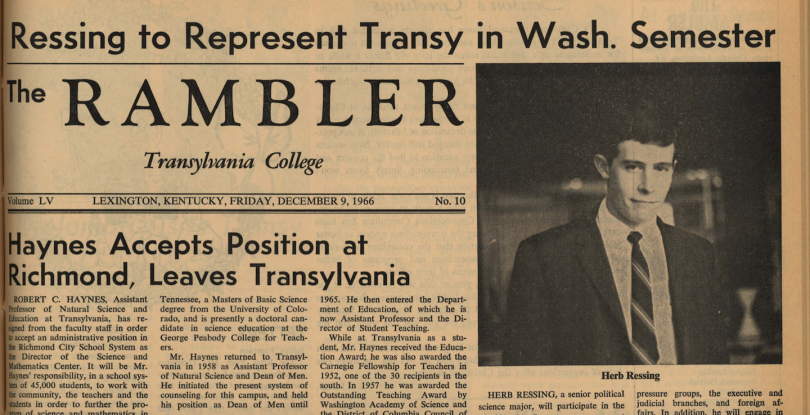

Their mentoring helped him grow and mature. “It was a good life,” Ressing reminisces. By 1966 he was married and living in a rooming house at the corner of Third and Broadway, accessible by the fire escape. He’s pictured in the 1966 yearbook and Rambler as a member of the debate awards team. Being on the team, he says, “taught me to think on my feet and to go off script in terms of not always having the right answers but being able to stick your foot in and give it a shot. It gave me a willingness to take some risks.”

“[T]he classes were small, the relationships with professors were big; it was not just in the classroom, it was everywhere.

Herb Ressing ’66

Next came the Washington Semester program at American University in Washington, D.C., which led to an internship and interesting jobs while he earned an MBA at George Washington University. Being allowed to attend the seminar in his senior year, he says “opened the door for going to a senator’s office and getting my foot in the door” first as a volunteer and then in a part-time job. Instead of being a shy intern, he says he had the confidence to say what he’d like to do and how he planned to do it.

When asked what was the most fulfilling part of his career, he pauses. “It’s beating all the odds. My father, who was very realistic, said, ‘You’ll never make it in D.C. It’s a cut-throat town.’ Not only did I make it, but I thrived in different careers. I worked on the Hill and ran presidential campaigns. I worked for the Republican National Committee and the Federal Trade Commission.” He then became a lobbyist to promote synthetic fuel. “Those are five different careers packed in 15 years,” he remarks.

Being able to adapt and thrive, he adds, comes in part from his liberal arts foundation. It kept him from having tunnel vision, he says. “You have an opportunity to view occupations, vocations in a broad sense of how it works. It’s really a product of being exposed to several different things in terms of political science, how politics works, and history, how we got to where we are today” (his major and minor respectively).

In an uncharted life, he notes, “I learned fairly quickly that you have to make your own opportunities.” He shares the revelatory moment in mid-life when his marriage had ended and his personal life was in flux. “It was like turning a page in a book.” He remembers walking down K Street in a suit, chasing jobs, when he stopped and said to himself, “You don’t have to do this anymore.” He’d long dreamed of sailing and a life on the sea.

So he bought Walter Cronkite’s sailboat from the Naval Academy. He’d already been teaching himself how to sail and earned a captain’s license. “I decided I’d like to go south to the islands. I’d been to the U.S. Virgin Islands, where I’d run a campaign.” When he settled in Ft. Lauderdale, his son joined him. He kept the boat behind his house and conducted charters, then expanded into yacht sales and marine development.

“It was very like everything else I’d done,” he says. “There was no blueprint on how to go about it. I just learned as I went and it worked.”

Laughter often punctuates Ressing’s narrative, but he’s serious about the importance of taking chances and risking failure. “I think the idea of not being afraid to try new things is the key. People make too much about being successful and too much out of failure; the thing is to be willing to take a gamble and experiment a little bit.”

Just as his first journey across the Atlantic as an undergrad was an unmapped adventure, “an interesting voyage that opened up all kinds of opportunities,” so too was his radical transition to an uncertain life on the sea. “A bunch of different things determine how it’s going to go, where we’re going to go,” he says of life. “And here I ended up in Florida.” He also met his English wife, Wendy Cox, while sailing.

Trading the halls of power for the soaring freedom of the ocean’s winds, Ressing revels in the variety of his life. With the Atlantic lapping at the edges of his yacht, he adds, “It’s very simple. Don’t be afraid to try new things. Period.”

Read more about his career transition from D.C. to Cronkite’s yacht.